As we’ve discussed in our recent market outlook commentary, traditional economic indicators such as shrinking GDP, stubbornly high inflation, and rising interest rates mislead 70% of economists who expected a U.S. recession in 2023. Now that we are three months into 2024, where are these indicators? And what has changed about the outlook?

January inflation data came out above expectations across the board. Core CPI (Consumer Price Index) YoY came in at 3.9% vs an expected 3.7%.[efn_note]Bloomberg. Access on 3/1/2024[/efn_note] CPI is like checking a grocery list to see how much the typical household basket of goods (clothes, rent, etc.) costs over time. It helps explain how our everyday living expenses are changing. Core PPI (Producer Price Index) YoY came in at 2.0% vs an expected 1.6%.[efn_note]Bloomberg. Access on 3/1/2024[/efn_note] PPI reflects how much producers are paying for goods and services, which can impact future consumer prices. Core PCE (Personal Consumption Expenditures) YoY came in at 2.8%,[efn_note]Bloomberg. Access on 3/1/2024[/efn_note] matching some expectations, but at the high end of the predicted spectrum. This is like taking a broader look at everything people spend money on, not just a fixed basket. It considers things like healthcare and services, giving a more complete picture of consumer spending and inflation, and making it the Fed’s preferred indicator. These hot inflation prints alongside accelerating wage growth data that came in at 4.5% for January vs its December reading of 4.3% have not made the Fed’s decision about whether to cut rates any easier.

Overall, a few bad prints are no reason to panic. These data points on their own likely won’t change the Fed’s rate cut trajectory. As of the time of writing, the futures market is pricing in a 62.5% likelihood that rate cuts start in June, and that jumps up to a 78% likelihood by September.[efn_note]Bloomberg. Access on 3/1/2024[/efn_note] Although the Fed futures curve still predicts three rate cuts in 2024, this seems too high, given how stable liquidity conditions have been. There has been an expectation shift among investors that quantitative tightening (QT) in aggregate will last longer than initially expected, past 2024 and into 2025, but at a slower pace so as not to repeat the liquidity crunch conditions of the 2018-2019 QT cycle. This opinion is supported by the Federal Open Market Committee’s (FOMC) January meeting minutes released last week.

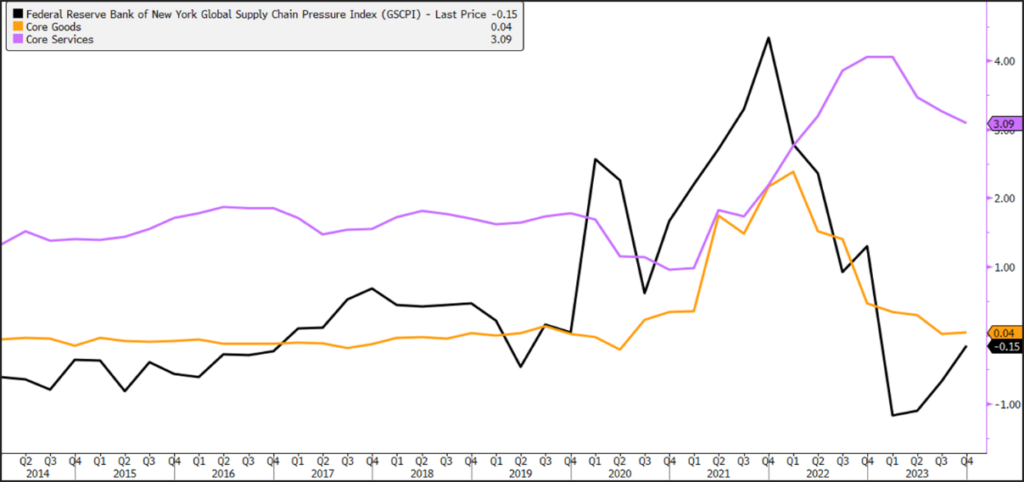

Despite these hot inflation prints and QT expansion talks, the long-term disinflation forces appear to still be intact. Overshoots in December GDP data have stabilized, the Zillow Rent Index is back at pre-pandemic levels, supply chain pressures have normalized, and quit rates have reverted to pre-pandemic levels, hopefully signaling that wage growth will follow.[efn_note]Shepherdson, Ian, and Oliver Allen. “United States Economic Monitor.” Pantheon Macroeconomics, 3 Mar. 2024. Accessed 3 Mar. 2024.[/efn_note] But it is becoming more evident every month that the path to sustained lower inflation will not be a straight line.

The main driver of these surprises in the January data was a result of the strong equity market rally and climate change. The uptick in portfolio-management services inflation component of PCE and the increase in dividend income, a component of personal income, were both a direct result of the stock market rally. As equity markets go up, the fees generated by asset-based portfolio management services increase, and as companies announce stock repurchase programs on the back of strong profits, fewer outstanding shares increase earnings per share and dividends per share. This feedback loop of stock growth supporting inflation makes it difficult to meaningfully cut down inflation while this market rally continues. These data points add credibility to our argument that to effectively push inflation down to 2%, equity markets must sell-off. Owner-equivalent rent (OER) and healthcare services are the other significant factors propping inflation. OER, which measures the cost of living in owner-occupied homes, had its most significant increase in a year. A possible explanation for this surprise can be attributed to a change in how it was calculated. “In January the proportion of OER weighted toward single-family homes increased by approximately 5%”.[efn_note]Shepherdson, Ian, and Oliver Allen. “United States Economic Monitor.” Pantheon Macroeconomics, 3 Mar. 2024. Accessed 3 Mar. 2024.[/efn_note] Another explanation could be that OER isn’t directly measured. Instead, it relies on estimations and assumptions, which can introduce inaccuracies in the short term. The healthcare inflation upward adjustment can be attributed to the 3.2% annual cost-of-living adjustment for Social Security recipients.

Going forward, geopolitical and climate risks make the path to sustained 2% inflation more difficult. Looking at these trends and data outlays through the lens of climate risk has helped our team maintain a stickier and higher inflation forecast than the market, which has benefited our portfolio positioning by allowing us to keep fixed income durations short. Looking at the graph below, the goods (orange) and services (purple) components of Core CPI, you can see that coming out of the pandemic, we had just about eliminated goods inflation, and we need only content now with services inflation. This has been the narrative for most of 2023, but as you can see, the Global Supply Chain Pressure Index (Black) has started to show pressure building again, a trend highly correlated with good inflation. Should we begin to see a re-acceleration in goods inflation, the Fed would find it nearly impossible to cut rates.

Climate risk is affecting these inflation datapoints. Global warming is intensifying the effects of the current El Niño, leading to a drought crisis in some of the most critical global shipping lanes. This crisis is being felt acutely in Panama, where severe drought, exacerbated by an intense El Niño event, has significantly impacted the Panama Canal. Reduced water levels have forced authorities to drastically cut ship crossings by over a third from a pre-drought capacity. This has resulted in a 20% decrease in cargo volume compared to the previous year’s fourth quarter and is estimated to cost the canal between $500 million and $700 million in revenue losses for 2024. Seeking alternatives, major shipping companies like Maersk are forced to reroute their vessels through longer passages, such as the Suez Canal (taking approximately 41 days to reach the East Coast of the US compared to the Panama Canal’s 35 days) or even longer detours, like sailing around

Cape Horn at the tip of South America. This situation highlights the growing vulnerabilities of global infrastructure to climate change. Food inflation is also on the rise. While some crops benefit from a warmer climate (i.e., Higher rainfall in California benefits avocados and almonds), many staple crops such as palm oil, sugar, wheat, rice, and corn will face more challenging conditions and falling crop yields. Sixty percent of global food production occurs in just five countries: China, the United States, India, Brazil, and Argentina, and rice, wheat, corn, and soy make up almost half of the calories of an average global diet. Given all of the above factors, one can see how climate risks can quickly create an inflationary environment.

Finally, energy prices have been one of the only deflationary components of CPI in 2023 and into 2024. In the intermediate term, non-Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) countries dominate medium-term capacity expansion plans for traditional energy projects. The relatively substantial increases from non-OPEC producers and the projected slowdown in demand for oil increase the spare capacity for oil in the intermediate term, keeping energy prices in check. Many investors need to pay more attention to the underestimated risks tied to a sustained rise in commodity price inflation. Capital limitations and the depletion of resources are poised to propel prices upward in the years ahead, contrary to the trends of the past decade. Consequently, investors still need to embrace this shift’s potential implications fully. We think the “end of oil” will be a function of price-related demand destruction, not technology-driven obsolescence (even though the cost curves for renewable power will help). Clearly it is in the interest of a fiduciary investor to consider climate risk when analyzing the macro environment and making investment decisions.